WELLNESS TOURISM

Wellness tourism is the powerful intersection of two large and growing multi-trillion-dollar industries: tourism and wellness. Holistic health and prevention are increasingly at the center of consumer decision-making, and people now expect to continue their healthy lifestyles and wellness routines when they are away from home.

In 2013, the Global Wellness Institute (GWI) unveiled the inaugural edition of the Global Wellness Tourism Economy report—a landmark study that defined the parameters and characteristics of the emerging wellness tourism sector, estimated its global size, and highlighted its far-reaching economic impacts. In that report, GWI first measured wellness tourism at $439 billion 2012. Since that time, wellness has become a major force in the global tourism market, with wellness tourism expenditures reaching $894 billion in 2024 (following a downturn in 2020 due to the pandemic). [Note that GWI’s most recent wellness tourism data can be found at: Wellness Economy Data Series.]

Five Key Things to Know About Wellness Tourism

1. What is wellness tourism?

The Global Wellness Institute defines wellness tourism as travel associated with the pursuit of maintaining or enhancing one’s personal wellbeing. With so much unwellness embedded in today’s travel, wellness tourism brings the promise of combating those negative qualities and turning travel into an opportunity to maintain and improve our holistic health.

2. Wellness tourism is not medical tourism.

Wellness tourism is often conflated with medical tourism—not only by consumers but in destination marketing. This confusion is caused by an incomplete understanding of these markets and inconsistent usage of terminologies by destinations, government organizations and promotion agencies. Sometimes the term “health tourism” is also used as a catch-all to describe many types of medical and wellness services and activities—from open heart surgery and dental care to destination spas and yoga retreats—causing further confusion. In fact, these two sectors operate largely in separate domains and meet different consumer needs.

A good way to understand the difference is to look at our health and wellbeing on a continuum:

- On the left are poor health, injury and illness. The medical paradigm treats these conditions. Medical tourism falls on this side—for example traveling to another place to receive surgery or a dental treatment because it is more affordable, higher quality, or unavailable at home.

- On the right side of the continuum is wellness—these are the proactive things we do to maintain a healthy lifestyle, reduce stress, prevent disease, and enhance our wellbeing. This is what motivates wellness tourism.

There is some overlap between medical tourism and wellness tourism—for example, DNA testing or executive checkups. But in general, the types of visitors, activities, services, businesses and regulations involved are very different between medical tourism and wellness tourism, even though they may share a dependence on a region’s basic tourism and hospitality infrastructure and amenities.

3. Who are the wellness travelers?

There is a common misconception that wellness travelers are a small, elite and wealthy group of leisure tourists who visit destination spas, health resorts, or yoga and meditation retreats. In fact, wellness travelers comprise a much broader and more diverse group of consumers with many motivations, interests and values.

GWI identifies two types of wellness travelers:

- Primary wellness traveler: A traveler whose trip or destination choice is primarily motivated by wellness.

- Secondary wellness traveler: A traveler who seeks to maintain wellness while traveling or participates in wellness experiences while taking any type of trip for leisure or business.

Importantly, primary and secondary wellness travel can be done by the same person on different trips, and these two types of wellness travel reinforce one another. Over time, some secondary wellness travelers will decide to take a primary wellness trip, as their interest in and experience with wellness grows. For example, a person who visits a day-use hot spring during a family vacation (secondary wellness travel) may later be motivated to plan a weekend getaway staying at a hot spring resort (primary wellness travel).

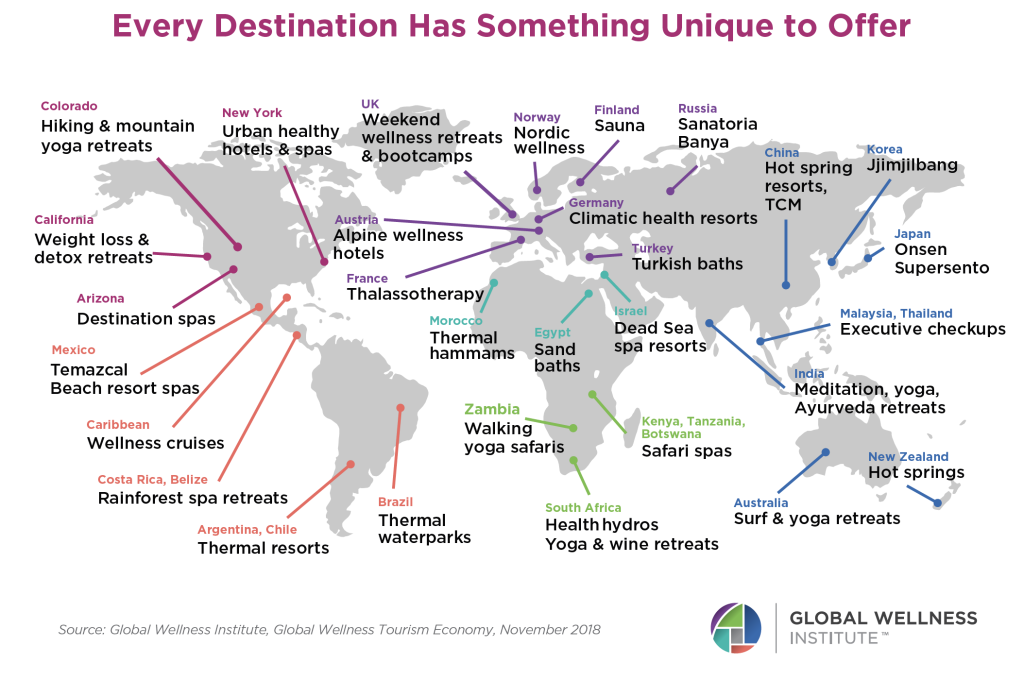

4. Every destination has something unique to offer to wellness travelers.

Like other forms of specialty travel, wellness travel is not a cookie-cutter experience. Every destination has its own distinct flavors in relation to wellness, linked with its local culture, natural assets, foods, etc. Some travelers may be satisfied with a generic massage, exercise class or smoothie. The more discerning and sophisticated wellness travelers—especially those in the millennial generation—are interested in what the destination offers that is different from someplace else. These unique and authentic experiences can be built upon indigenous healing practices; ancient/spiritual traditions; native plants and forests; special muds, minerals and waters; vernacular architecture; street vibes; local ingredients and culinary traditions; history and culture; etc. Because each destination is different, there is always something unique to offer wellness travelers.

5. Wellness tourism brings benefits to businesses and stakeholders beyond the wellness sectors.

The wellness tourism economy is much larger than a narrowly defined set of typical wellness businesses, such as spas, wellness retreats, thermal/mineral springs and boot camps. Wellness travelers (especially secondary wellness travelers) are looking to continue their wellness lifestyle during travel, and this lifestyle may encompass healthy eating, exercise/fitness routines, mind-body practices, nature experiences, connections with local people and culture, etc., thereby creating opportunities for businesses such as yoga studios, gyms and fitness centers, healthy food stores/markets, events, arts and crafts, museums and many others.

In addition to wellness experiences, all wellness tourists need transportation, food and lodging, and they will likely seek out shopping or entertainment. All of these businesses—whether they are wellness-specific or not—benefit from wellness tourism and are part of the wellness tourism economy. There are numerous opportunities to infuse wellness into all kinds of amenities and services, which can help businesses differentiate, provide more value, and capture higher spending by wellness travelers. Examples include airport spas that target wellness travelers in transit; wellness-centered hotels for those who want better sleep and regular fitness routines; specialty restaurants serving healthy, organic or local cuisine; transportation companies that use clean fuels or low-/zero-emission vehicles; or gift shops that sell products that are connected to unique local wellness traditions.

Wellness tourism may help destinations mitigate the negative impacts of mass tourism or over-tourism. Because wellness travelers tend to be high-spenders and favor experiences that are authentic and unique, there is less pressure for destinations to engage in a “race to the bottom” strategy that competes on price and quantity.

Wellness tourism also provides destinations with an opportunity to reduce the seasonality of visitor flows. For example, ski destinations can attract wellness travelers interested in hiking and other outdoor activities in the summertime, while beach destinations can appeal to travelers looking for a more tranquil environment to de-stress or take a retreat in the wintertime.

Measuring Wellness Tourism:

GWI defines wellness tourism as travel associated with the pursuit of maintaining or enhancing one’s personal wellbeing. We measure wellness tourism by aggregating the trip expenditures of people who are defined as wellness tourists. These expenditures include lodging, food and beverage, activities and excursions, shopping, in-country transportation (travel within the country), and other services (e.g., concierge, telecommunications, travel agent services, travel insurance, etc.). We include expenditures made by both international and domestic travelers:

- International wellness tourism expenditures: All receipts earned by a country from inbound wellness tourists visiting from abroad, with an overnight stay.

- Domestic wellness tourism expenditures: All expenditures in a country made by wellness tourists traveling within their own country, with an overnight stay.

Within each of the international and domestic tourism segments, we estimate the portion of trips and expenditures that are represented by wellness tourists, including both the primary and secondary wellness tourism segments (as defined above). We aggregate the spending of primary and secondary wellness tourists, both international/inbound and domestic, across 212 countries, to arrive at the size of the global wellness tourism industry.

For more information:

- GWI’s 2024 report, Wellness Policy Toolkit: Wellness In Tourism, explores barriers that are currently preventing wellness tourism from delivering broad-based health and well-being benefits, and it presents six policy ideas that help everyone – from visitors to local residents to businesses – reap more benefits from tourism.

- In 2018, GWI released an updated Global Wellness Tourism Economy report, which provides in-depth analysis and data for the sector.

- GWI’s 2020 white paper Resetting the World With Wellness: Travel and Wonder explores why the rapid growth of travel has resulted in an unhealthy industry and how wonder, awe and connection can be wellness-enhancing and help us reconnect with our purpose for travel in a post-COVID-19 future.

- GWI’s wellness tourism figures are also updated and released every few years in the Global Wellness Economy Monitor. For the most recent wellness tourism research, see Wellness Economy Data Series.

- Additional information and resources are available through GWI’s Wellness Tourism Initiative.