At its essence, physical activity is about movement. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines physical activity as “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure – including activities undertaken while working, playing, carrying out household chores, travelling, and engaging in recreational pursuit.” The benefits of physical activity are varied, widely proven, and well-known, including: preventing chronic disease, reducing stress, managing weight, strengthening functional mobility, improving sleep, alleviating depression, improving cognitive function, and so on. To receive these benefits, our engagement in physical activity needs to be regular, consistent, and sustained – not intermittent, only during holidays, or only when we want to lose weight or can find the time.

The wellness world often looks at physical activity through the narrow lens of “fitness” or “exercise” – working out at a gym, taking a spin class, running on a treadmill, lifting weights, doing yoga or Zumba, and so on. In fact, we can do wellness-enhancing physical activities in many ways and places. GWI research explores the different ways in which we can engage in physical activity, from fitness, recreational, and leisure activities, to the natural movement that occurs in our daily lives.

At its essence, physical activity is about movement. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines physical activity as “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure – including activities undertaken while working, playing, carrying out household chores, travelling, and engaging in recreational pursuit.” According to the WHO, in order to maintain good health, children and adolescents need 60 minutes of moderate- to vigorous intensity physical activity daily, and adults need 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity, or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity, on a weekly basis. The benefits of physical activity are varied, widely proven, and well-known, including: preventing chronic disease, reducing stress, managing weight, strengthening functional mobility, improving sleep, alleviating depression, improving cognitive function, and so on. To receive these benefits, our engagement in physical activity needs to be regular, consistent, and sustained – not intermittent, only during holidays, or only when we want to lose weight or can find the time.

The wellness world tends to look at physical activity through the narrow lens of “fitness” or “exercise” – working out at a gym, taking a spin class, running on a treadmill, lifting weights, doing yoga or Zumba, and so on. In fact, we can engage in physical activities in many different ways. Physical activities are broadly divided into two categories: natural movement and recreational physical activity.

- Natural movement encompasses the physical activities that are essential to our daily lives, including transportation (e.g., walking and cycling as transportation), occupational (e.g., work that requires manual labor) or domestic (e.g., household chores, gardening, etc.) movement. These kinds of activities have been the core of physical activity for humankind for millennia. Unfortunately, natural movement is now on the decline around the world, progressively discouraged by our modern sedentary lifestyles and car-centric built environments.

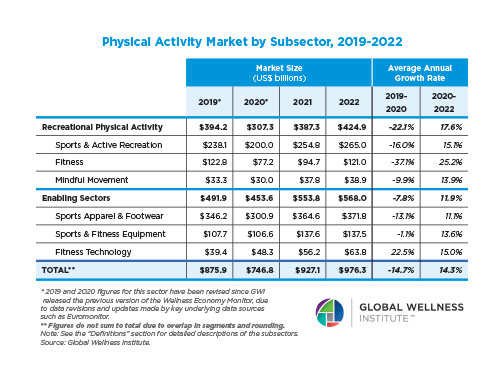

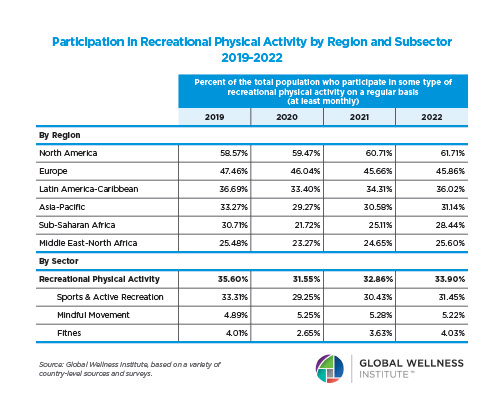

- We also engage in optional and intentional movement as part of our hobbies and leisure time. Recreational physical activity can include going to the gym, playing sports, taking a walk or cycling for fun, dancing, children playing on a playground, and much more. GWI divides recreational physical activity into three categories: fitness (gym- and equipment-based workouts like spinning, treadmill running, weight training, cardio classes, etc.); sports and active recreation (e.g., team sports like basketball or football, individual sports like tennis or swimming, outdoor sports like skiing or bicycling, martial arts, dance, etc.); and mindful movement (e.g., yoga, tai chi, qigong, Pilates, stretch, barre, etc.).

If we engage in enough natural movement during our daily tasks, then it is not necessary for us to compensate with recreational physical activity in order to meet WHO guidelines and stay healthy. This is the case, for example, in the world’s “Blue Zones” – places with very high life expectancy, where living environments encourage routine natural movement. This is also the case in many lower income countries. Uganda, for example, was rated the “most active” nation in The Lancet’s 2018 physical activity study, with only 5.5% of adults physically inactive – because people walk to work, do manual jobs, grow their own food, and have to stay active to survive.

In most of the world, however, our living environments, jobs, and lifestyles are less and less conducive to natural movement, while recreational physical activity is becoming increasingly essential in order to stay healthy.

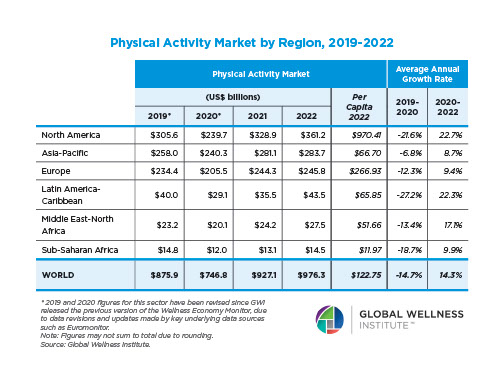

- See GWI’s full report, Move to be Well: The Global Economy of Physical Activity, for more information on the different types of recreational physical activities and detailed country-level data on consumer spending and market sizes around the world.

- See the GWI report, Build Well to Live Well: Wellness Lifestyle Real Estate and Communities, for more information on the critical role that the built environment plays in supporting both natural movement and recreational physical activity.